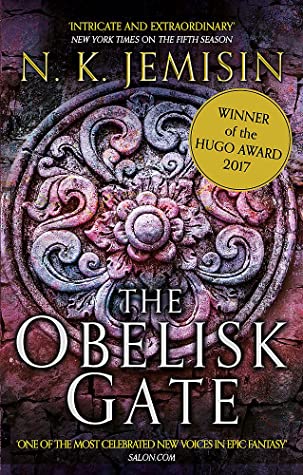

The Broken Earth Trilogy

N.K. Jemisin

“Just because something is horrible does not make it any less true,” the narrator of N.K. Jemisin’s Broken Earth trilogy tells us in the closing pages of her epic tale. This would appear to be the guiding philosophy for the series, which takes an unflinching look at social injustice, environmental destruction and a global economy built on, and reliant upon, exploitation.

Dealing with reality is the only option for Jemisin’s characters, because survivors of a climate apocalypse don’t have the luxury of alternative facts.

Having reviewed the first novel in the series, The Fifth Season, I was going to discuss the second and third installments (The Obelisk Gate and The Stone Sky) separately, but I was so immersed in this world that I finished Sky before I could even begin to write about Gate.

To briefly summarize, the Broken Earth trilogy follows Essun, a mother with special talents who wants to improve a broken world for her young daughter. She lives in a future where Earth has become a barren, inhospitable planet prone to sudden tectonic cataclysms and unpredictable seasons.

When we first meet Essun, her husband has murdered their infant son and kidnapped their daughter, Nassun. This sends Essun on a quest to rescue her only living child. Both Essun and Nassun are “orogenes” — a race of people who can manipulate the earth’s energy to magical effect, such as quelling or generating earthquakes, or creating protective energy shields.

Orogenes are both feared by the majority (known as “stills”) and necessary to the survival of the community. Therefore, orogenes usually live only as long as they are useful, but as Jemisin writes in Gate, “being useful to others is not the same thing as being equal.”

This results in brutal treatment and ostracization. Being an orogene in the wrong neighborhood can be fatal, and those with little talent are often killed in their youth. Orogenes with advanced skills are sent to special schools akin to the church-run American Indian boarding schools of the 19th and 20th centuries.

This injustice is best encapsulated in the following passage:

“They’re afraid because we exist. There’s nothing we did to provoke their fear, other than exist. There’s nothing we can do to earn their approval, except stop existing — so we can either die like they want, or laugh at their cowardice and go on with our lives.”

Jemisin’s writing is moving, inspirational and tackles social issues without being didactic. She is also honest. There is no happy ending tacked on in the final pages. There is no ultimate justice.

There is no way to completely fix a broken world, even if Essun can successfully end the catastrophic “seasons.”

But beyond the social commentary is a thrilling tale of perseverance, adventure and familial bonds. The scenery is vivid and well-crafted, and the magical system is revealed with minimal exposition. I found the community-building aspects more engaging than the battle sequences, but there are no weaknesses to Jemisin’s game — evidenced by the fact that each installment in the series won the Hugo Award for Best Novel from 2016-2018.

The Broken Earth trilogy is an engrossing epic, but it is also a scathing indictment of humanity’s pathological reliance on exploitation in order to prosper. Fittingly, these novels emerged at a time of rising nationalism and white supremacist activity. Jemisin offers a concise description of the fear fueling these movements:

“There are none so frightened, or so strange in their fear, as conquerors… Conquerors live in dread of the day when they are shown to be, not superior, but simply lucky.”

We have seen the deadly consequences of this in recent years. The Broken Earth trilogy may not prescribe a sure-fire remedy to this struggle, but it is a piercing battle call to keep up the fight.