Proud to be a Dystopian

by Vince Darcangelo

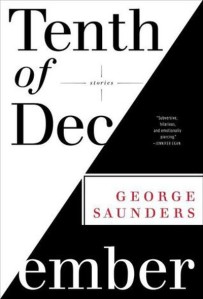

It was a warm autumn evening at the Gramercy Theater, Oct. 5, opening night of the 2012 New Yorker Festival. The room was thick with literati, and on stage were three heavyweights: Jennifer Egan (A Visit From the Goon Squad), Margaret Atwood (The Handmaid’s Tale) and George Saunders, whose new collection of short fiction, Tenth of December, was released on Tuesday, Jan. 8.

heavyweights: Jennifer Egan (A Visit From the Goon Squad), Margaret Atwood (The Handmaid’s Tale) and George Saunders, whose new collection of short fiction, Tenth of December, was released on Tuesday, Jan. 8.

The theme of the panel was “Utopia/Dystopia,” and Atwood led off with a brief history and deconstruction of the genre. Utopias and dystopias go hand in hand, she said, because with any utopian idea “there’s always a catch, and the catch is this: Everything’s going to be fine, but first we’ve got to get rid of these people.”

And then we came to Saunders, whose works, such as the exquisite CivilWarLand in Bad Decline, often contain dystopian themes or settings, along with healthy doses of humor and satirical absurdism.

“I never really thought I’d write a dystopian (story),” he said, adding that he first tried to emulate iconic writers like Hemingway and Raymond Carver. It wasn’t working, so he tried something different.

“If I set something in a theme park or the near future,” he said, “the language comes alive.”

And thus, a great writer, and celebrated literary subversive, emerged.

#

Tenth of December is a short and bittersweet 10-tale offering of gripping short fiction, incorporating science fiction and otherworldly elements (similar in tone, in my opinion, to Kurt Vonnegut). The book’s opening tale, “Victory Lap,” which originally appeared in The New Yorker in 2009, concerns an attempted abduction of a teenage girl and the hijinks that ensue.

That’s right, hijinks.

As silly as it is serious, it is the humor that sharpens the dark edge of “Victory Lap.” This is a bold piece of work. Saunders takes chances by shifting points of view and writing from the interior voice of teenagers, but he pulls it off as only he can. There’s a jazzy rhythm and flow to the piece, and it deserves to be read aloud. The story really came to life for me when I heard Saunders read it at the University of Northern Colorado in 2010.

Probably my favorite story from Tenth of December is “Escape from Spiderhead.” It has the classic elements of his fiction: people in the near-future in a seemingly powerless position; the intertwining of corporate and institutional control; wacky goings-on; funny, yet fitting, product names; and an unlikely hero who somehow manages to carve out his acre of humanity within this madhouse.

Specifically, our hero, Jeff, is a convict in a research prison, where his punishment is to be a lab rat for chemical experimentation. As part of a sex study, he is given drugs that create feelings of intimacy and attraction to another person; another that induces loquacity; a performance enhancer (Vivistiff™) that makes Viagra seem like a sugar pill; and another chemical that lowers one’s “shame level.”

The experiments take a dark turn when he is enlisted in a Darkenfloxx™ study. As Jeff describes the drug: “Imagine the worst you have ever felt, times ten. That does not even come close to how bad you feel on Darkenfloxx™.”

The scene is reminiscent of the notorious Milgram experiments, and it concludes brilliantly—somehow both uplifting and tragic. It’s a reminder that great literature doesn’t resolve with the hero winning or losing, but rather redefines what it means for that character to win or lose.

“CivilWarLand in Bad Decline,” for example, is set inside a rundown theme park overrun with violent gangs (to the point that the Civil War re-enactors pack live ammunition in their muskets). The protagonist is a working-class dreamer and father of two who endures disappointment and the threat of violence for the sake of his family. But his idea of winning and losing changes in this theme park.

“Sea Oak,” from his 2000 collection, Pastoralia, is a genre-bending story incorporating new-wave male strippers, a post-industrial ghetto and a dead aunt who refuses to go away. Likewise, it concerns a poor family burdened with violence, and takes a fantastical turn that recalculates the stakes for all involved.

“Sea Oak” won an O. Henry Award Prize and was also nominated for a Bram Stoker Award. How many Bram Stoker nominees have received gushing praise from the New York Times?

#

At the heart of Saunders’ fiction are class issues (he comes from a working-class background and earned an engineering degree from the Colorado School of Mines); the impact of an ever-invasive corporate culture (see “I CAN SPEAK!™” from 2006’s In Persuasion Nation); and the absurdity of the modern workplace.

An example of the latter in Tenth of December is the story “Exhortation,” which is told in the form of a memo from a boss to his underperforming crew. The memo is in reference to “March Performances Stats” and attitudes toward the work being done. He begins by comparing their duties to cleaning a shelf, but of course, it becomes apparent that their labor is far more sinister:

“Even you guys, you who do what must be done in Room 6, don’t walk out feeling so super-great, I know that, I’ve certainly done some things in Room 6 that didn’t leave me feeling so wonderful, believe me…”

Whatever goes on in Room 6, it clearly has nothing to do with shelves. This story calls to mind Saunders’ classic short story, “The 400-Pound CEO,” concerning a worker drone whose job is to kill raccoons for the company Humane Raccoon Alternatives.

In both of these stories, Saunders guides us through a sausage mill as unpleasant as any Upton Sinclair encountered. We see characters doing menial and often unpleasant work, and manipulative and often cruel bosses attempting to put a positive spin on their duties, if for no other reason than to create a healthy façade for the buying public. Greed and rampant corporatization has left the working class in the absurd position of having to abase themselves and others to get by.

I can’t think of a better description of dystopian fiction. Often, the term calls to mind an enslaved, automated world gone grey: a dramatic vision complete with conflicts worthy of the Thunderdome. But with Saunders, the dystopia is more workaday, which makes it all the more chilling.

For Saunders, it’s a way “to say here’s the way we look at habituated reality,” he said at the New Yorker Festival. His fiction breaks the surface of this habituated reality, and it offers us a fresh and not-always-pleasant look at our daily lives.

But it’s not all bad. It’s a world filled with humor, even if it’s of the gallows variety. It’s populated with colorful and unexpected heroes, bizarre-yet-feasible scenarios, and it’s always a fuzzy line between winning and losing.

“For me, the ideal position is to say, yes, it’s horrible,” Saunders said, “but yes, it’s wonderful and let these two things play out.”